Architects “step back into the playroom” with Lego

Currently the only LEGO Architecture that set has been released for 2018 is for one of the world’s most populous cities – Shanghai – and boasts 597 pieces. Here Shaun Soanes investigates how stepping back into the playroom with building bricks can inspire even the most established designers.

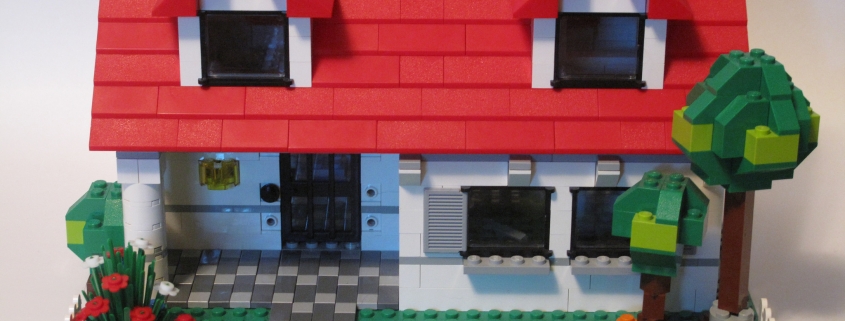

Like many architects – and indeed professionals in the built environment – my interest was spiked as a kid. I would spend hours constructing complicated LEGO structures, towers, bridges and homes, flexing my creativity and pushing the boundaries of possibility.

This might serve to explain why since 2009, 32 models of world famous landmarks including Big Ben and the Leaning Tower of Pisa have been launched as part of the Lego Landmark series and why in 2014 – after more than 60 years of firing up children’s imaginations – the toy manufacturer launched Lego Architecture Studio aimed specifically at the likes of me.

Block party

The Architecture Studio was the first Lego set that comes without instructions, providing 1,200 white and transparent bricks and a 250-page manual for inspiration, featuring contributions from a number of high-profile architects, all extolling the virtues of using Lego in their creative process.

The kit was designed to “allow you to explore the ideas and principles of architecture” exploring ideas such as scale and mass, surface and section, modules and repetition. There are no little yellow people as their fixed scale of 1:48 would limit construction to that ratio but there are flat baseplates, chamfered wedge-shaped blocks and lots of tiny pieces with nipples and sockets sprouting in all directions.

Far from being a quick way to throw together an idea, building with Lego requires planning and precision. It takes forethought. Will your structure be balanced and not tip over? Is the base wide enough to support it?

Questions for designers

There is no doubt about it, toying with Lego blocks presents a hands-on opportunity to learn the basics of design as well as structural engineering.

Scale is everything. After all, you want to build something that’s big enough for your toy minifigure and his friends and the same concept applies to architects creating spaces large enough to accommodate a desirable number of people. Building to scale also puts building materials into perspective, requiring you to admit their limitations. The bigger the structure, the more ease you’ll have incorporating curves and arches into it, even while using rectangular bricks.

Live in Lego

The link between Lego design and real-life architectural design took one step closer in October last year when the fantasy of inhabiting a Lego house became reality In Billund, Denmark. Lego unveiled the Lego House — a 130,000-square-foot building that is equal parts experimentation lab, prototype testing grounds, and shrine to the colorful bricks.

From the street, the building looks white. It’s only from above that viewers can gaze upon the multi-colored roofs and outdoor seating. The structure was created in partnership with architecture firm Bjarke Ingels Group, which designed the structure, and began construction in 2014.

Initially, it used as its model a small-scale replica made from (big surprise) Lego bricks. The 1:100 model toured the world, stopping in places like Switzerland, France, and the US. It also visited BrickCon, one of the largest Lego conventions in the world, in Seattle, Washington.

Lego in the East

In Bury St Edmunds, a Lego project at St Edmundsbury Cathedral is underway. The Cathedral and the mother church of the Diocese, is being recreated entirely of Lego bricks while raising money to protect the future of the building itself.

As architects, we have been heavily involved in projects to repair, restore, renovate and reorder churches of this size and stature and couldn’t think of a better way to link fundraising and fun. By donating £1 per Lego brick, visitors to the church can help it reach its ambitious target to raise £200,000. It’s also a chance to be involved in a project of national significance, being only the fourth Cathedral in the UK to be interpreted in this way.

Modelling the future

Architects have long used scale models to demonstrate the reality of their design to clients.

These models are appealing to clients aesthetically while conveying valuable information and help designers plan using a range of materials, styles and scales.

Most architectural models are made using acrylic, foam, timber, veneer, card and 3d printed plastics. They can also be painted with colour to represent building materials and etched to achieve texture.

Perhaps in future some architects might consider using Lego bricks to show clients what can be achieved using a bit of imagination? After all, unlike traditional cut-and-glue model making, which is totally inflexible once built, this is a snap-together system which allows continuous modification and enables client participation in the design process.

It’s certainly worth considering.

The Christies

The Christies